Stuart Harris

Ship name / Flight number: Empire Star

Arrival date: 19/08/1947

I was born in Tottenham, London on 14 March 1931. As a child, I was gradually aware how the power dynamics were shifting in Europe and to a degree how the ascendency of Hitler and the Nazis would have an impact on my childhood and education.

My father was a fitter and turner. He volunteered as a local air raid warden prior to and during World War II. My mother raised my older brother, Leslie, and I. Leslie joined the parachute regiment of the army as soon as he was old enough. Because London was a prime target for German bombs, I, like many other children, was sent to live with a family in the countryside. It was 1939 and I was just eight years old. I lived with a family in Hertford for nearly two years and continued primary school there. I can remember lying on the grass watching the planes fly overhead. Often there’d be dog fights in the sky.

The separation from my family caused a break in the bond with my mother that I don’t think was ever fully resolved. In 1941 I came back to London to do the eleven-plus exam, which is a standardised exam given to children at the end of primary school. It is used to determine whether you can go to a grammar school, or have a less academic education, such as learning a trade or book-keeping. I was lucky that I passed and got a scholarship to Tottenham Grammar School. There we would collect shrapnel and splinters of bombs anti-aircraft shells.

While I was at school in Tottenham, I remember the playground was hit by a German V1 rocket. It was lunchtime, and myself and two other students used to bring sandwiches, instead of paying for a meal, so we were outside. My two colleagues were blown against a brick shelter and killed. I was around the other side of the shelter, for reasons I don’t recall, so I was shielded from the impact of the blast. The science laboratories were all destroyed.

From an early age I started collecting stamps, which I think contributed to my interest in history and geography. I followed the progress of the war as Germany invaded Russia, and Russia invaded Finland and so on. I read lots of books about World War I and II, and I think that contributed to my interest in International Relations later in life. I matriculated but my parents couldn’t afford to send me to university, so I looked for work. I tried a few different things, until I got a job in the taxation department in London, which would later help me get a job in Sydney.

In 1946 I saw an advertisement in the newspaper for the Big Brother Movement and was attracted to Australia for two reasons. First, I followed cricket, and Keith Miller (an Australian test cricketer and all-rounder) was an attractive sportsman to me. Secondly, a friend’s family billeted two friendly Australian airmen during the war, and I thought that if Australia was full of people like them, then it must be a good place. Further, it was very cold in England in the 1940s and we didn’t have much fuel for our fires – Australia looked warm and sunny in comparison. There was also lots of talk about what Britain would do now the war was over. People were concerned that all the soldiers would come back and take all the jobs. I was also concerned about the effect of the British class system on my parents, and on society generally. When my supervisor at the tax department asked me what I wanted to do in the future, I said that I wanted to go to university. He advised me to ‘consider your station in society and where you are meant to be’. I knew that what he was really saying was, ‘stay in your class, mate’. That stuck with me, quite strongly. I think it made me more determined to leave. I didn’t come out here specifically to get away from the class system, but by doing so, I did get away from the class system.

My brother, who was seven years older than me, made it through the war alive, and I was able to see him before I left. He went to Durham University on an ex-serviceman’s scholarship and later emigrated to Australia and lectured in Physics at the University of New South Wales. I was surprised by how easy it was to get my parents to agree to my coming to Australia. Eventually, they decided to join me. I think my father could see some of the problems and challenges that England would have to confront and he probably persuaded Mum.

I sailed to Australia in 1947 on the Empire Star. It was both a cargo and a passenger ship, so our route and timing were set by the needs of the cargo we were picking up and dropping off. One of our first stops was at Tenerife on the Canary Islands, which are off the west coast of Africa. I was excited to be visiting some places I had collected stamps from! Coming from England where the weather and mood was grey, it felt strange to see music and dancing and people on holidays having fun. Our next stop was South Africa.

Mostly the trip was enjoyable. We were looked after well, and enjoyed the free time and outings in different ports. We docked in Melbourne and then caught the overnight train to Sydney. When we arrived in Sydney, we went to Sloan’s bakery and I met my ‘Big Brother’, who took us out for the afternoon and showed us around the city. Soon, I was sent to Temora, where I was billeted with a farming family. I was told, but not shown how, to help round up the sheep. I was pretty hopeless at this. Then I was told to chop wood for kindling, but because the wood had been sitting there for ages, it was difficult to split, so I wasn’t good at that either.

The first family I stayed with were very religious, but if I had been religious, I wouldn’t have been a Methodist. I think they were good people, but we didn’t get along. Mr Mansell from BBM organised my transfer to Ivor Anderson’s wheat and sheep property in Pucawan, which was a good move. He was a nice chap and I stayed with him for a year and a half. He had more of an idea of training people, instead of just telling them to do something and expecting them to know how to do it.

Anticipating the future when my two years were up, I asked Ivor Anderson how I could earn some more money, more than the basic wage that he was obliged to pay me. He said: ‘well, I’ve got eight dairy cows on the farm, and if you get up at 5am and milk them, we’ll send the milk to Victoria and you can keep the profit’. I did this for a while until the cows dried up.

I decided to try my hand at something different and get jobs with other farmers. We put up fences, built dams and harvested wheat. I remember working on the platform of the wheat harvester, filling and sewing the bags of wheat as it came out of the harvester – bloody hard work. I left once the harvest was in.

I caught up with another Little Brother, who was sent out that way – Vic Bartlet. He was only a bicycle ride away. We stayed in touch all our lives. Later on, he worked with me in Sydney. I also kept in touch with my parents and stayed in Sydney when they decided to emigrate to Australia.

After I’d done my two years with the BBM in the country, I went back to Sydney and did odd jobs. I had saved some money and borrowed enough from my parents to buy a truck and set up a small delivery business. Ivor Anderson had helped me to get my truck driver’s license. It was a difficult time because petrol was still being rationed, but I managed to get enough. I did deliveries during the day and worked for Goodyear Tyres on the night shift, building tyres. My parents bought a small property in western Sydney and I’d try to sleep in between jobs.

The area we lived in had many poultry farms, and I carted eggs from the farms to the Egg Marketing Board. One day, a big, six-foot tall poultry farmer approached me and asked if he could buy my truck. I said it wasn’t for sale. He insisted that I should sell it to him, and we argued for a while. He was imposing and looked fierce. During our forthright discussion he said to me: ‘I don’t mind competition but I don’t like opposition’. That made me keen to go to university to find out what the difference was! I eventually sold the truck back to the place where I bought it from, for a good price, in March 1952.

Eventually I applied to the Public Service Board for a job. Fortunately, my matriculation results were good enough that I could bypass the public service exam. They allocated me to the Tax Department. In the 1950s, parts of Australia were very sectarian. The Tax Department was staffed by Catholics, so it was rare for a Protestant like me to be working there. But they were very good to me. The tax department offered concessions to study at university, so I successfully applied and enrolled in an economics degree at the University of Sydney. In theory, I was given five hours off work each week to go to classes, but I wanted to do the course at the same pace as the day students, so it was a heavy study load largely at nights. It took me four years to complete the course, exiting with an upper second-class honours degree.

Because I lived out west, I had to get up at 6am to catch a steam train into the office, do my work, then go to evening classes, catch the train home, eat dinner about 10pm, write my essays and sleep for a few hours before getting up at 6am to start all over again. I was so very tired that I used to fall asleep at my desk. Both my supervisors knew that I was sleeping on the job but they didn’t try and wake me. They were both Catholic, and they knew I wasn’t, but they didn’t do other than help me.

As well as helping me through university, the tax office also introduced me to my future wife. We met at a departmental sports day, playing tennis. Pamela was also studying at the University of Sydney and we struck a chord. She was only 19 years old when we got engaged and, while she was undertaking a Bachelor of Arts Degree, we were married in 1958. In the meantime, I got a job with the Tax Department in Canberra, and would come back to Sydney every second weekend to see her. Once we were married, we decided to settle in Canberra, because houses were hard to get, and the public service would provide us with a house. After my mother died of tetanus, my father moved to Canberra to live in a ‘granny flat’ with us.

Left: Pamela Harris, nee Manning, 1958.

I was promoted from the Tax Department to the trade portfolio, and started working for John Crawford in the policy secretariat. There were not many public servants in the 1950s with degrees in economics, particularly with honours, so Crawford started to use me as his personal research assistant, even after he left the Tax Department to work at the Australian National University (ANU). The first major experience in this sense was working on the government-established Committee of Economic Enquiry for developing policies for economic growth – The Vernon Committee in 1965. Some years after the Vernon Report (The Committee of Economic Enquiry) I was asked to chair a committee on the principles of rural policy in Australia. Crawford was initially invited to chair it but said he’d prefer to be a committee member under my chairmanship.

John Crawford helped me to apply for a public service fellowship to the ANU, and I studied import controls, which John was in charge of administering. When I was awarded a second fellowship, Crawford suggested that I turn it into a PhD, which I did. By working in the evenings and weekends, I completed my PhD. My thesis was on the control of imports, which was a major issue in Australia in the late 1950s.

Crawford retired from the public service in 1960 and became Professor of Economics at ANU. I continued working in the area of trade policy, often with Crawford. When I was in the Department of Trade, I was asked to write political speeches for the Minister for Trade, John McEwen, prior to the 1961 election. I objected, because the public service is meant to provide impartial advice. This didn’t go down well, and I was told that if I stayed in the trade department, I wouldn’t get promoted. Alf Maiden (head of the Bureau of Agricultural Economics (BAE)) suggested that I apply for the position as Senior Economist with the BAE, which Crawford had established in 1945. I did, and I was successful. I think my credibility was enhanced by those couple of years that I spent working on farms through BBM.

Above: Pamela, Stuart, Jan and David Harris, c. 1963.

In 1967, I took the opportunity to work on land reform and agricultural development in the Colombian Planning Department in Bogota, Columbia, a country I knew almost nothing about. I went there with my young family – Pamela and my children, Jan and David. I worked there for a year and a quarter; it was fascinating. The country had just come out of a civil war and the political situation was still volatile. There were threats of kidnapping and people being held for ransom. There were only a couple of times when we were seriously fearful – such as when some of the windows of our house were smashed after we declined to pay protection money. We were careful to always travel in convoy with other families if we went outside the city. Our third child, Richard, was born in Bogota.

When we returned to Canberra in 1968, I was put in charge of the BAE. One of the things I did in this role, was to establish the annual Agricultural Outlook Conference, which the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry continues to convene each year. When I heard a media report from a leading scientist advocating the use of vast tracts of sandy land in Western Australia to grow wheat to feed the booming population in Asia (who prefer rice!), I was concerned. Our research was showing that this would hasten land degradation. The annual Outlook Conference came about because I was looking for a way to increase the BAE’s competitiveness and the public’s attention to our research. It largely worked, and is still working. In the BAE, and later in the Department of Trade, I was active in the promotion of regional economic cooperation, attending conferences and publishing articles on farm adjustment as well as government reports.

I’ve had two patrons in my career: John Crawford and Bob Hawke. They have both helped me and recognised my skills. When I was Director of the BAE (1968-1971), Hawke would ring up wanting information for his basic wage case, which he was preparing for the ACTU. He always went to the top, so he contacted me, as the Director. He would ring up and say: ‘I want x,y,z.’ I’d reply: ‘I’ll ring you back when I have gathered the information’. He’d counter: ‘No, I’ll leave the phone line open’. He did that when he went to China, and was criticised for the long-distance call costs!

I worked with Doug Anthony, the new Minister for Agriculture in the Fraser Government, formulating the Farm Adjustment Program for the wool industry. My association started in the Whitlam era when there were a number of inquiries. The first was the Vernon Report on which I worked at Crawford’s behest, crafting a critical paragraph on using tariffs and the exchange rate as instruments of economic management. Secondly, I chaired a government committee of inquiry into rural policies, publishing The Principles of Rural Policy in Australia in 1974. Membership of the committee included Crawford. The Rural Policy report was criticised by some economists because of the reference to tariff compensation. They saw this as microeconomic policy rather than a macroeconomic policy instrument, preferring to use the exchange rate as a policy instrument in certain circumstances.

Australia was active in pursuing south east Asian development, in part for trade benefits and in part to counter the influence of communism. I was active in economic cooperation. I spent considerable time with Australian and regional economists in forums of economic cooperation which eventually led to the establishment of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

After five years as Director of BAE, I moved to the Department of Overseas Trade as Deputy Secretary. I was involved in a number of research projects, and one of the reports was criticised by the former Prime Minister, Sir Robert Menzies, and the then Secretary to the Treasury, John Stone. Paul Tilley has recently written a history of the Australian Treasury Department, and he interviewed me for his book, which gave me a belated opportunity to counter some of their criticisms. (See: Changing Fortunes: A History of the Australian Treasury, 2019).

In 1975, I chaired a subcommittee of the Royal Commission on Australian Government producing a report on Economic Policy Formulation, which led to the separation of the Department of Finance from the Department of Treasury. This was not a recommendation of the subcommittee; but it said it could be done without creating any problems and this was used by Malcom Fraser as a justification to split them.

In about 1975, Crawford asked me if I was interested in a chair at the ANU. I was appointed Chair of Resource Economics in the recently established Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies (CRES). I didn’t find the transition from a government bureaucracy to academia too jarring, as I’d been writing and editing research reports in government. While I was at ANU, I asked Bob Hawke to contribute a chapter about trade unions for a book I was editing about globalisation. Hawke sent in his chapter, and I provided him with some feedback, and through that process, I got to know him better.

I can remember doing a very early piece of research and writing, possibly the first piece, for the Australian Academy of Sciences on global climate change and the need for an ecologically sustainable approach to economic development. I, along with colleagues at CRES, had spoken to several people about the need to consider ecological sustainability alongside economic development and Bob Hawke became an advocate for our work. Paul Keating replaced Bob Hawke before we could use some of the volumes of research that had been produced. Keating partly absorbed it, in relation to Antarctica, but didn’t put any effort into implementing the rest of the findings. What he did for protecting Antarctica was useful and he deserves credit for that, but the rest of our climate initiative effectively died out.

I was elected to the Academy of Social Sciences as a Fellow in 1982. I kept my economics up through a lot of international work, including with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). This led to working in foreign affairs when Hawke was Prime Minister.

I’d been asked by a committee of public servants if I’d be interested in being considered for the role of Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs. I didn’t expect to be offered the job. Hawke discussed my appointment with Bill Hayden, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, and advocated for having someone with an economics background in the role. I eventually agreed to accept the position in 1986. I wrote a report on what foreign affairs is supposed to be, and some people tell me they still regard my Review of Australia’s Overseas Representation as the ‘bible’, when it comes to foreign affairs.

I travelled with Hawke overseas a lot, with Hayden’s agreement. Hayden and Hawke didn’t always get along, as Hayden had reluctantly resigned the leadership of the Labor Party in 1983 to allow Hawke to take over. In 1987-88, I oversaw the amalgamation of the Department of Foreign Affairs with the Department of Trade. It was always going to be messy, but the fact that Foreign Affairs was to be the bigger partner and subsume the trade portfolio, made it more difficult. After about 12 months as the Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, I went back to ANU, to the School of International Relations. I’d had some disagreements with Hayden about staffing. I’d said to myself, if I lose sleep at night over my job, I’ll quit – so I did.

I became conscious of the increasing power and importance of China during the early 1970s. I first visited China with the Deputy Prime Minister, Jim Cairns in 1973. Once Prime Minister Gough Whitlam re-established diplomatic relations between Australia and China, I knew China would be increasingly important to Australia’s economic and military security. To put it simply, I was interested in China because that’s ‘where the money was’! I still think we have a poor understanding of Chinese beliefs and values, which results in Australia making big mistakes. I think there’s two reasons why Australia’s relationship with China has been so up and down. First, fear of China has been in our blood for a long time. Even though China has never moved to attack Australia, we still harbour fears of Chinese expansion into Australia. Secondly, Australian leaders are thinking primarily about how they can talk to the top people in America, at the expense of our trade, security and economic relationships with China. Americans have an inbred sense of superiority, which doesn’t help them in their approach to foreign policy. I’ve been impressed by China’s ability to do things, not by their rational approach to what they choose to do. The American political system is not a rational one in many respects. I suspect the Chinese concern about Australia is partly because we have access to American troops, and also, Chinese people who come to Australia presumably have an opposition to the Chinese government.

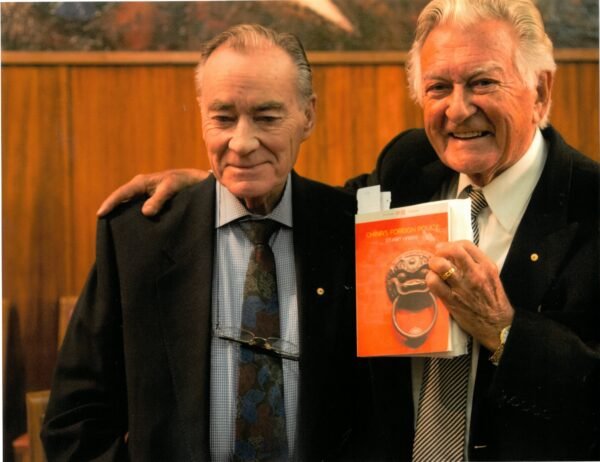

My last book, China’s Foreign Policy, was launched by Bob Hawke in 2014. I think only people who have spent a bit of time in China, like Tim Fischer, the former leader of the National Party (from 1990-1999), have come close to having a sensible approach to China. Scott Morrison did a lot of damage to Australia’s relationship with China, which it will take time to repair.

Left: Stuart Harris and Bob Hawke at the launch of Harris’s book, China ‘s Foreign Policy, 2014.

In the early 1990s, I worked in the post-graduate part of ANU, lecturing undergraduate students on China and I taught a postgraduate course on China with two colleagues. I specialised in China’s external affairs and their position in the world. I retired from ANU in 1996, but continued researching and writing as an Emeritus Professor of International Relations. Unfortunately, I developed Parkinson’s Disease 2013 but managed with some difficulty and help from my carer to write the book China’s Foreign Policy. Parkinson’s has affected my mobility and my eyesight has deteriorated, so I can’t read easily.

My wife, Pamela, supported me throughout my career and enjoyed the travel opportunities it provided. She trained as a guide at the National Library and latterly took an interest in Aboriginal Art. Together, we had five children – two of whom have pre-deceased me. Once our children were at school, Pamela worked in the public service in the Environment Department and travelled to Brazil and South Africa with her work on organic pesticides. I have no doubt that she could have been a top public servant, if she hadn’t had children.

At one stage, the Big Brother Movement approached me to lobby Bob Hawke on their behalf, to allow them to continue their discriminatory youth migration scheme, which was only open to young people from Britain. I declined, saying that I believed in a ‘melting pot’ (of many cultures). I’ve been in many hospitals where the nursing staff, with very few exceptions, come from overseas. The Nepalese staff especially, make an unpleasant experience pleasant.

I think my decision to travel to Australia when I was 16 years old was one of the few sensible decisions I’ve made. The way England was progressing, and has gone, made it a good time to emigrate. I feel the English conservatives in Britain have no concept of the ‘lower orders’ and what it’s like to be working class. I found opportunities to advance in a way that I couldn’t have done in Britain – I’ve had two tremendous careers. I’m grateful to the BBM for getting me here. I probably wouldn’t have come, apart from that.

Left: Stuart Harris, 2023